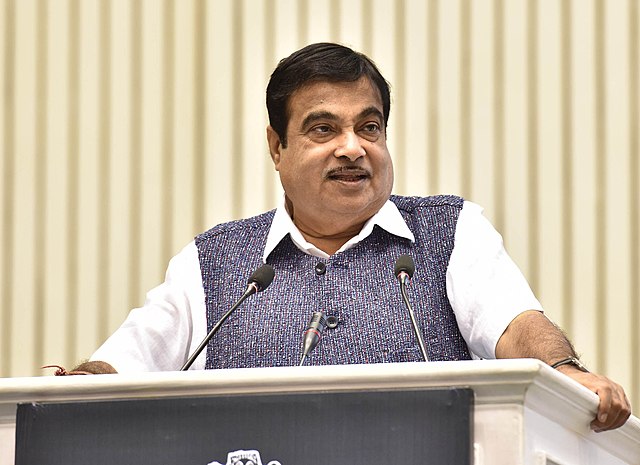

Nitin Gadkari lately suggested that subsidies for electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers may no longer be necessary, is grounded in some valid observations. As the EV technology has matured, production costs have seen a decline, and consumer hesitation towards purchasing EVs has diminished. India’s EV market share reached 6.3 per cent last year, marking a significant 50 per cent increase from the previous year.

On a global scale, EVs captured over 15 per cent of the market share in 2023, with China dominating 60 per cent of worldwide sales. The EV subsidy structure typically encompasses three main aspects: support for production, development of charging infrastructure, and incentives to influence consumer behavior. These components are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Without a reduction in production costs, consumer adoption would be limited. Similarly, purchasing decisions are heavily influenced by the availability of charging infrastructure.

European countries like Germany and France have discontinued production subsidies while maintaining purchase credits for consumers. The withdrawal of production subsidies was necessitated by their strain on government budgets, but this has consequently slowed the electric transition for European automakers. European consumers have become more cautious about EV purchases, harboring doubts about their governments’ ability to subsidize charging infrastructure adequately.

The United States presents a unique case due to its natural advantage in producing fuel-injected cars, thanks to cheap oil. Additionally, under Donald Trump’s leadership, Republicans have been skeptical of climate change, further complicating the EV landscape in the country.

Japan maintains a cautious stance towards EVs as the most efficient pathway to energy transition. The Japanese automotive industry has made significant investments in hybrid vehicles, which are gaining traction as EV subsidies are being scaled back in various markets.

Underlying these regional variations is the growing dominance of subsidised Chinese automakers in the EV market. There’s increasing resistance from markets against becoming dumping grounds for inexpensive Chinese EVs. Governments are also becoming wary of the substantial costs China has incurred in subsidizing infrastructure and buyers.

The United States, European Union, and Japan are now focusing on protecting their respective automotive industries during this energy transition period. Continuing a race to the bottom with production subsidies may no longer be a viable strategy. While India is a relative latecomer to this transition, it may need to reassess its EV subsidy policies to account for these evolving global dynamics.

This situation highlights the complex interplay between technological advancement, market forces, government policies, and geopolitical considerations in shaping the future of the automotive industry. As the global landscape of EV production and adoption continues to evolve, countries like India will need to carefully balance their desire for a cleaner transportation sector with the economic realities of their domestic industries and the broader global market trends.