‘Beware, the ides of March’. In the Tragedy of Julius Caesar, Shakespeare famously wrote about a real-life soothsayer who tried to warn the Roman emperor of imminent danger. On March 15, 44 BC, on the steps of a Roman amphitheatre, a group of mutinous senators assassinated Julius Caesar.

In March 2020, almost exactly two millennia later, as I marvelled at the grandeur of Gerasa, an ancient Roman city in Jordan, that ancient prophecy came back to haunt the world in a far more virulent manner. I had been in Jordan for a week when the coronavirus’ shadow began looming over countries in the Gulf and Africa. I’d been guilty of completely ignoring travel advisories when I’d landed in Amman a few days back.

Amman—where skyscrapers share the skyline with ancient Roman citadels—the capital city of Jordan exemplifies the country’s fascinating blend of the modern and the historic. It was the latter that interested me; for a taste of that, as well as a slice of local life, all roads, as the locals like to say, lead to Downtown. Chalky, box-like homes blanket the hillside at the city’s older, more traditional eastern quarter.

Fridays are weekly holidays in Jordan and Downtown is swelling and ebbing when I visit. Milling with people out with their families, shopping at souks, street food vendors busily handing out shawarmas, and buskers perched on street corners singing lilting Arabic melodies that rise above the hubbub. Things to buy here, if you are so inclined, are spices: there’s sumac, which you’ll find sprinkled on Hummus, and Za’tar a blend of sumac, thyme, roasted sesame seeds, marjoram, and oregano that makes simple pita bread taste like a delicacy. In Jordan, the ubiquitous Shawarma is nothing like anything I’ve ever had. This middle-eastern street food staple has been honed to an art form here.

As the story goes, Cleopatra got her lover, Roman emperor Mark Anthony to invade the region just so she could have her dose of the the Dead Sea’s famous black mud.

The lowest point on earth, famous for its natural buoyancy and restorative black mud has continued to be one of the world’s favourite getaway for a spot of rejuvenation and beauty therapy. Still jet lagged from my 20-hour journey from India to Jordan I’m only too happy to fall into this hyper-saline lake’s buoyant embrace.

My reverie is broken by a concerned beach marshal who suggests I stop splashing about. “…the salty water can blind you if it enters your eyes,” he admonishes. It might be a dream cocktail for spa enthusiasts but apparently the water can even choke a person who happen to swallow a fair bit. You’d better be dead serious in the Dead Sea.

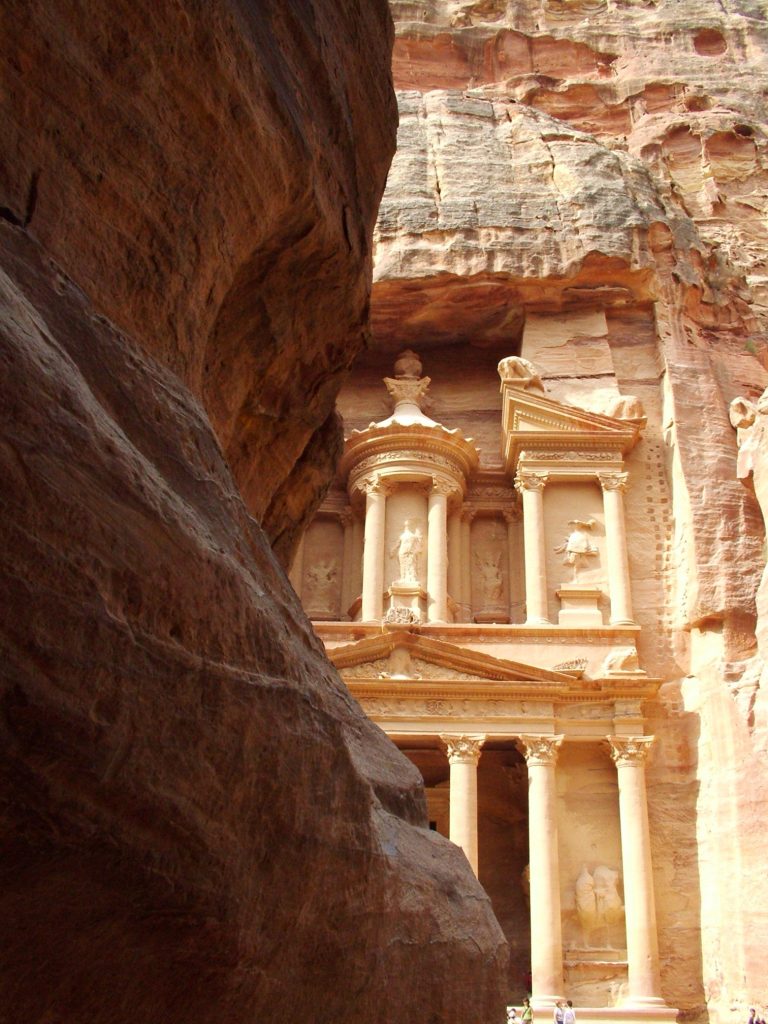

A ‘rose-red city half as old as time,’ wrote John Burgon, a 19th century poet, fantasising about the ancient city of Petra in modern-day Jordan. Unbelievably, Burgon never visited Petra, but the 2000-year-old settlement in the desert fired his imagination obsessively, as it has for writers, adventurers and explorers through the ages. Entry to the ancient city of Petra is via ‘The Siq:’ a fissure in the sandstone mountains at Petra. It pretty much nails the visual dramatisation of the Holy Grail that it was presented as in the Harrison Ford-classic, ‘Indian Jones and the Last Crusade.’

CREDIT: CC WIKIPEDIA COMMONS

The Siq has water channels, stone carvings, camel caravans and betyls (famous god blocks) set in niches. But these elaborate carvings are merely a prelude to one’s arrival into the heart of Petra, where the Treasury, or ‘Khazneh,’ a monumental tomb, awaits to impress even the most jaded visitors. Now, a chalice with the promise of eternal life is hard to beat but visitors walking through the Siq are greeted with a dramatic reveal of Petra’s most magnificent edifice. Carved into the rock-face in the first century BC, the Treasury is absolutely, superlatively, monumental.

From the Treasury, the ‘street of facades’ leads to a large open area. On one corner lies the Great Theatre that has obvious Roman influences in its architecture and on the other side lies the impressive urn tomb. The Monastery, one of the largest structures in Petra was actually a large dining hall. Petra was an entire Hellenistic city with over 800 structures that housed over 20,000 inhabitants. Forget about seeing it in a day, it would be near impossible to do so in a week. Petra is expensive and the difference between a day pass and anything longer is nominal. If you can make the time then it pays to opt for the latter.

Jordan’s religious and cultural pluralism is reflective of its long historical significance with different faiths. The life and times of one figure in particular hold significance spanning different faiths. Moses or Musa Ibn Imran, in Islam, Christianity and Judaism is believed to have died and been buried at Mount Nebo.

According to the Bible, Jesus of Nazareth was baptised by John the Baptist in the Jordan River. The Baptism site, is considered one of the most important sites in Christianity.

Given that, it’s no small surprise that Madaba, a small town an hour’s drive from Amman, is considered Jordan’s most important Christian site. I’m on my way to Mount Nebo via Madaba when the heavens open up. Jordan’s weather takes a leaf from the dramatic landscape. It turns chilly and hot within the same day and golden sunshine gets washed out by pouring rain in a matter of minutes, or kilometres if you’re on the road.

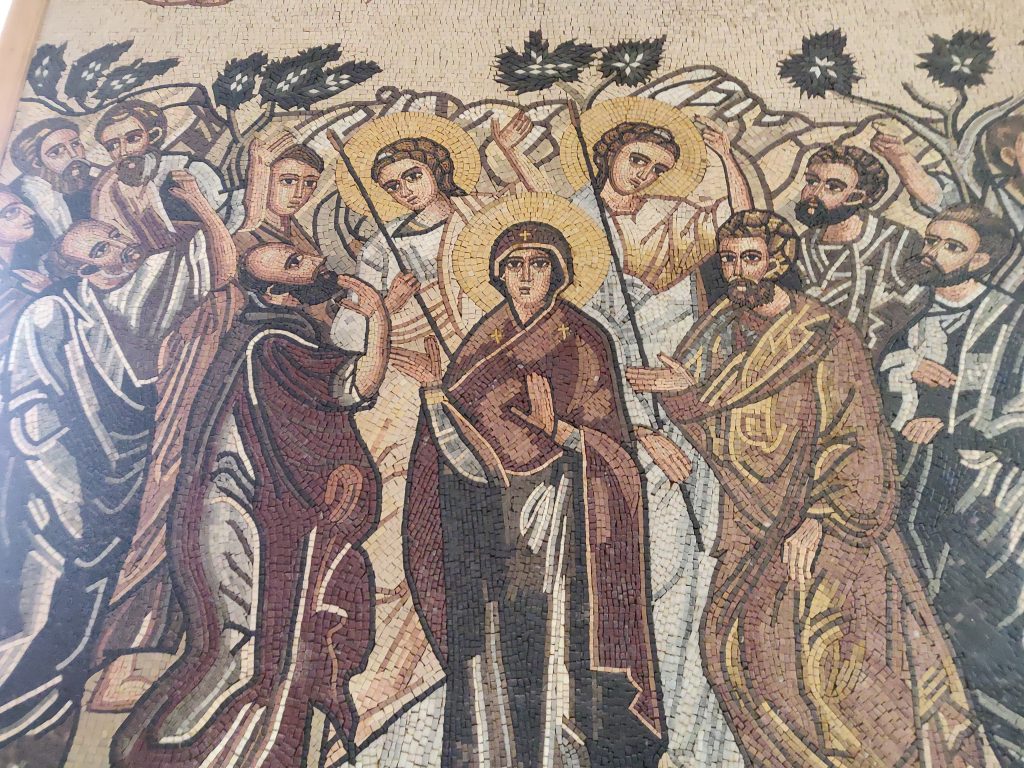

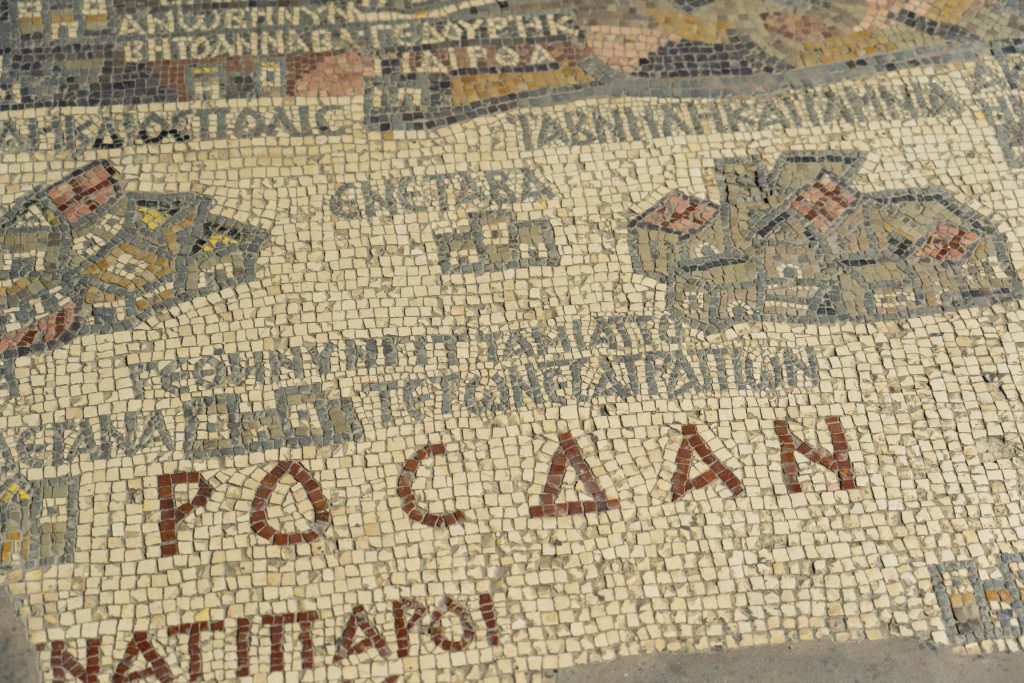

Madaba’s relevance lies inside the byzantine-era church of St. George, specifically, on its floor: where a map made from mosaic tiles was discovered in the late 19th century. The map lists out 157 major Biblical sites including areas north of the Jordan River and the Dead Sea. Two thirds of this sixth-century mosaic was destroyed by an earthquake in 746 AD. but the ancient cities of Jericho, Jerusalem and Bethlehem can be clearly seen.

‘Let there be light.’ The Gods smile by the time I make my way to Mount Nebo. The heavens clear and I’m witness to what qualifies, surely, as a mythological, if not historical scene. According to varied religious text, Moses and his followers reached Mount Nebo and this is where they had their first glimpse of the Promised Land. The Jordan Valley stretches out in front of us with a hint of Dead Sea revealing itself to the west, Israel, Jordan and the West Bank in the distance.

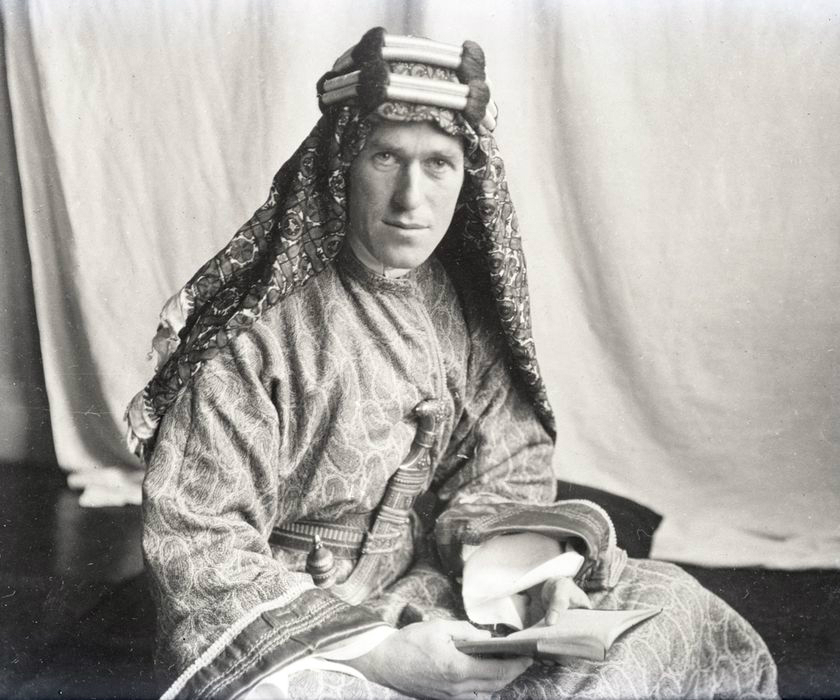

As we drive north, the topography changes and we make our way into the desert that makes up almost two thirds of Jordan. The North Arab Desert stretches into Syria, Iraq and Saudi Arabia but is at its most spectacular in Wadi Rum that literally translates into ‘Valley of the Moon’. Wadi Rum lies in the far south of Jordan, and east of the Rift Valley. It’s a protected region stretching across an area almost as large as New York City. What differentiates Wadi Rum are the spectacular sandstone arches, towering cliffs, and natural gorges: all coming together to create a spectacular landscape. It was here, that TE Lawrence—a young English military intelligence officer—convinced a rag tag army of Bedouins to traverse across Wadi Rum and attack the Ottoman stronghold of Aqaba in the early 20th century. Wadi Rum had never been crossed by camel before, not even by the Bedouins. The rest, as they say, is history.

The ‘desert safari’ is standard tourist fare in Wadi Rum, and is well worth the time—I spent almost an entire day being ferried about in an SUV to different corners of Wadi Rum. The petroglyphs carved in prehistoric times are especially spectacular—the arid weather has preserved every line etched on the rocks.

For me, a side trip to an etching of Lawrence’s face carved into a rock face by the Arabs, to formalise his inclusion into their ranks for eternity is accommodated on special request. “ Not too many people remember that film,” muses my guide.

to attack the Ottoman stronghold at Aqaba. CREDIT: CC WIKIPEDIA COMMONS

Everyone remembers Matt Damon’s ‘The Martian,’ and you’ll find a queue of selfie-seekers waiting to park themselves on a rock that Damon’s character sat on while pondering on his fate after being marooned. Great as that film is, it can’t hold a candle to Lawrence’s real-world exploits. As astonishing as Wadi Rum is, that feat of human endeavour is what this desert will be remembered for.

The Martian has contributed to a slew of martian-style campsites that now dot this landscape. I’m staying at one, and it does look, well like a colony on another planet. Repasts though are traditional Bedouin affairs. For dinner the chef prepares a Zarb—a subterranean barbeque—that’s been simmering for over three hours. Back in the day the nomadic Bedouins needed to cook with minimum equipment and burying meats in an oven with hot coals was the norm.

As larger-than-life this desert is, Wadi Rum is also a fantastic milieu for star-gazing. The expansive night sky mirrors the sweeping firmament of Wadi Rum that has been preserved largely unchanged through the millennia. To Jordan’s credit, there are no massive concrete resorts, no touristy shops selling trinkets here. Wadi Rum is still, much bigger, and much grander, than the men who inhabit it.

The next day begins with a long drive to the city that Lawrence attacked—Aqaba. Jordan’s favourite holiday destination, Aqaba is all about sun-kissed loveliness and you can see Israel and Egypt clearly, lying across the water on the other side western banks of the Red Sea. Stirred by crystal clear waters, Aqaba’s stirring cocktail of middle-eastern culture and a laid-back beach holiday vibe is refreshingly bracing.The beaches in are lined with resorts and day-visitors like me can pay a daily fee and use the facilities.

Home to some of the most pristine coral reefs in the world, the Red Sea is a Valhalla for diving and snorkelling. If you’re looking for the holiday vibe then head straight to Aqaba which also has the country’s only other international airport. I decide to drop off the rental car and take a flight back to Amman.

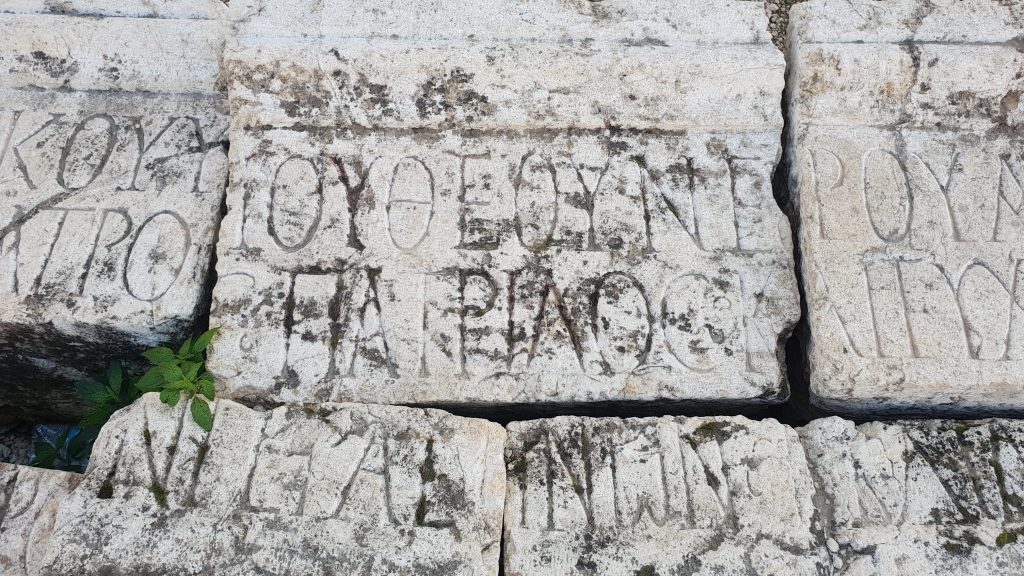

Just about an hour’s drive out of Amman lies the city of Jerash that takes its name from the ruins of an ancient city that lie within it—Jerash. For centuries, Jerash, had thrived by leveraging its location on the King’s Highway—an ancient trading route in the Levant. One of the easternmost outposts of the Roman empire, Jerash was the most impressive of the Decapolis—ten semi-autonomous city-states under the Roman empire.

Historical accounts describe Jerash as a monumental city. Not hard to imagine given how astonishing it still is. Two massive temples, one dedicated to Zeus, and the other to Artemis, occupy the vantage points looking down at an Oval Plaza that leads to a colonnade, amphitheatres, plazas, and residences.

The Temple of Artemis, was one of the few structures that survived the earthquake that destroyed Jerash in AD 749. It was converted into a fortress by soldiers from Damascus in 1120 AD. The very next year, Baldwin II, the King of Jerusalem conquered and destroyed the temple. The ruins have survived, natural catastrophes, wars, fires, and destruction wrought by men, who came and went. Unlike all the great empires and kings, who created, ruled over, and tried to destroy Jerash, the city has endured; cocking a quiet snook at human frailty.

It’s a sobering thought, especially in context of the global catastrophe that engulfed the world in 2020. It was on the steps of a roman amphitheatre in Jerash that I got a call from the Indian embassy— I was to be repatriated to India the very next day, unless I wanted to risk getting marooned in Jordan.

On the airplane back I thought about what we’re doing to the planet and how much that’s responsible for the pandemic. Geologists say that the environmental damage which human beings have inflicted on the planet will reverse itself in our absence. All we’ll leave are cities like Jerash. Striking reminders of humanity’s astonishing capabilities, and, its monumental follies.