Drifting is like the middle child of racing – slightly unhinged, performative to the core, and ostentatiously rebellious.

While racing as a sport celebrates speed and rewards the first one to reach the finish line, drifting, as the name suggests, steers away from the conventional parameters of victory. Just like a typical middle child, it fiercely challenges the established order by showcasing over-the-edge action, theatrical display of power and above all, the spectacle of momentarily losing control only to regain it in the most cathartic fashion.

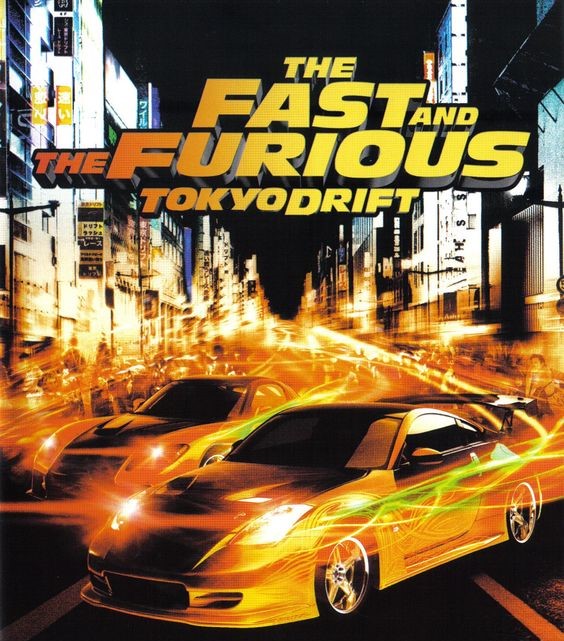

The fascinating spectacle of cars sliding sideways through challenging bends with tyres emitting plumes of smoke creates a captivating visual. This cinematic appeal of drifting did not escape Hollywood’s discerning eye, and they skillfully translated this exhilaration to the big screen in ‘The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift’.

Before the film’s release in 2006, drifting had already begun to permeate American mainstream culture, with Japanese drift subculture making its way through professional drift events and mass media. However, the movie offered the audience a global introduction to the world of street racing and drifting, reshaping perceptions of these phenomena on a global scale.

You cannot talk about drifting without talking about Keiichi Tsuchiya aka Drift King. Not only did he feature in Tokyo Drift, he has also been extremely pivotal in popularising drifting as a mainstream motorsport around the world. In 1987, Tsuchiya secured funding from garages and publishers in the street racing scene to produce videos. His initial videos showcased his exceptional skills as he drifted a Toyota AE 86 GTV Levin along the Usui touge – a picturesque mountain pass near Nagano and Keiichi’s home track.

Drifting in motorsports subsequently gained prominence in 1999 with the advent of the D1 Grand Prix in Japan. Tsuchiya’s narrative served as a source of inspiration for countless enthusiasts, as he embarked on his journey from grassroots origins, including street racing, mountain pass drifting, and self-made car modifications. What truly distinguished street drifting and events like the D1 Grand Prix, aside from the legal constraints, was the evolution of evaluation criteria and brand identity.

Drifting thrived in urban streets and mountain locales, assessed primarily as an art form and a display of driving skills, irrespective of legal implications. This culture gave rise to car enthusiast groups, often referred to as “zoku,” shaping a community of nonconformists and social outsiders. Street racing unfolded on public roads and secluded streets, sometimes attracting the Yakuza or Bōsōzoku groups for a leisurely drive.

In essence, mastering the art of car drifting, whether on the streets or on a designated course, hinges on the synergy of appropriate equipment, an acute sense of balance and individualistic style. As the Drift King aptly put it, “Speed isn’t everything; you’ve got to look good on the touge too.”

In 2003, the United States played host to the D1 Grand Prix in California, a pivotal moment that spawned spin-offs of this motorsport competition in many Western countries. Notably, Formula D emerged in 2004, inviting drivers from around the world to compete but primarily taking place within the United States. Eventually, Formula D evolved into a highly lucrative sport, attracting substantial sponsorships to support the technical standards and training required.

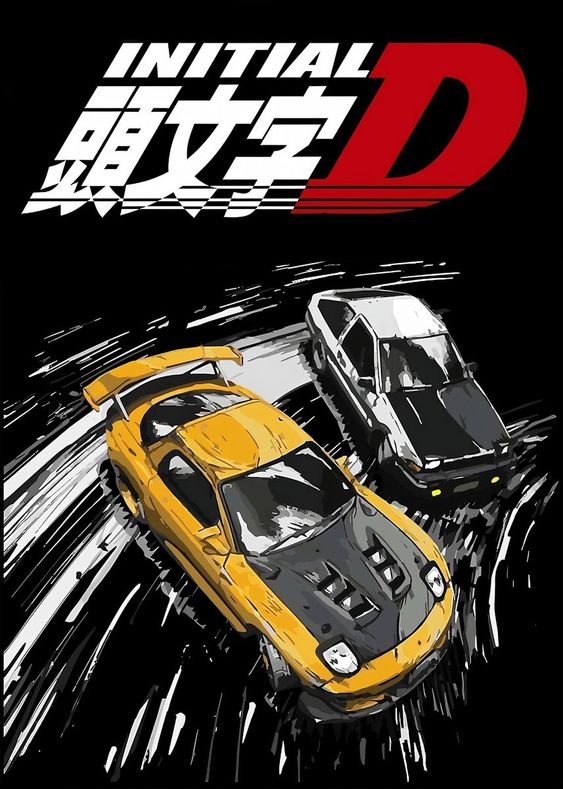

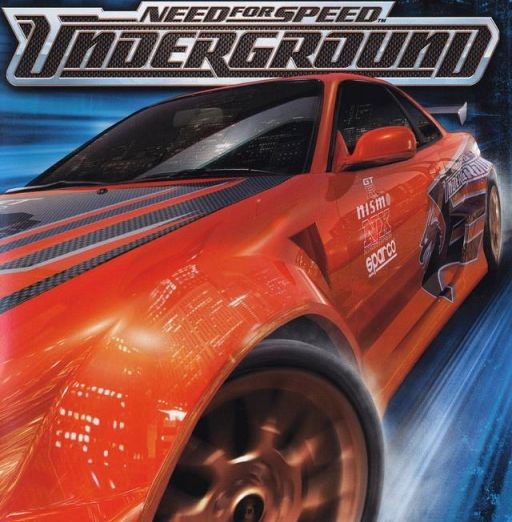

The surge in the popularity of drifting culture was also propelled by the popular Japanese manga series ‘Initial D’ that delves into the realm of illicit Japanese street racing. The narrative is set in idyllic mountain passes and characterised by the art of drifting. The manga weaved some very clever insights into the storyline with the editorial guidance by Tsuchiya. The popularity also spiked with the emergence of American drifting video games in the 2000s, exemplified by the ‘Need for Speed: Underground’ franchise and ‘Gran Turismo’. These games allowed players to customise and race exotic cars in an illegal street drifting narrative, with the franchise itself amassing a remarkable 150 million copies sold.

The humble beginnings of drifting in Japan and its integration into American pop culture and the commercial market prompt us to contemplate the prevalence of a new hybrid culture emerging between these two nations. While there are signs of fusion, such as the prominent display of Monster stickers and other sponsored brands, and American actors narrating the tale of Japanese street drifting, it is apparent that Western influences play a dominant role in shaping this culture.

This cultural exchange appears unidirectional rather than the symbiotic relationship that hybridity implies, where cultural traits and knowledge are exchanged evenly. Mass media has facilitated America’s ascension to the forefront of the global drifting scene, both economically and visually. Drifting initially entered American pop culture as the flashy portrayal of “Japanese Street driving” and subsequently evolved into a professional and amateur sport with distinct American commercial undertones.

However, it is worth noting that this emerging culture seems to lack the dynamic interplay between Japanese drift culture and the American drift scene. What appears as a one-sided pull towards economic gains for America is manifest through the influence of television, video games, car imports, manufacturing, and heavily sponsored events.

Drifting, originally deeply embedded in Japanese car culture, has transcended geographical boundaries to become a prominent feature in various motorsport disciplines. Within the realm of rally driving, drifting assumes a pivotal role, allowing for artful power slides on treacherous gravel surfaces. Celebrated rally drivers like Ken Block, Rhys Millen, and Travis Pastrana have effectively made the transition to drifting, along with the WRC champion Kalle Rovanperä who made his debut in the Drift Masters European Championship this year.

Banger racing, reminiscent of a demolition derby, offers a thrilling and demanding form of motorsport characterised by deliberate vehicular collisions. Meanwhile, in South Africa, the vibrant Spinning culture emerged in the 1980s, evolving into a dynamic spectacle featuring luxury cars drifting to the point of destruction in townships, accompanied by music, dancing, and exuberant participation by children. In the Middle East, the fervour for drifting thrived, culminating in events like the Red Bull Car Park Drift competition, which places a premium on the precision of car control and skill over sheer speed.

Coming to the Indian motorsport landscape, it’s safe to say that drift culture is still young but very much alive. Drifting has been slowly gaining popularity with the youth but the road to enter the mainstream is long and quite frankly, arduous. Recently, for the first time in the history of Indian motorsport, an official Drift Challenge was organised by JK Tyre and held in the parking lot of Buddh International Circuit (BIC) in October. Organised in a controlled environment, this one-day event, backed by the Federation of Motor Sports Clubs of India (FMSCI), made a significant mark in the Indian drifting scene. Winner of the event, Chandigarh’s Sanam Sekhon drove a specially prepared Lexus GS 300 to victory in two out of three categories.

Drift culture in India is aspiring to align itself with the global standards and with the emerging drift clubs and training programs, the future of drift culture in India looks positively promising.