When the Biden administration unveiled new U.S. auto-emissions regulations in March, it marked a significant shift in strategy compared to earlier proposals. The revised rules, which allow for a slower transition to electric vehicles (EVs) and greater reliance on gas-electric hybrids, have raised questions about their long-term environmental impact.

Easing the transition to EVs

Initially, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed converting two-thirds of new vehicles to EVs by 2032. However, the final regulations lowered this target, permitting automakers to comply by producing more gas-electric hybrids. This adjustment reflects a concession to the auto industry, which had expressed concerns about the feasibility of a rapid transition to fully electric fleets.

Pollution reduction claims

EPA Chief Michael Regan asserted that the relaxed rules would still achieve similar pollution reductions as the original proposal. However, a Reuters examination of the rule changes and emissions projections reveals that the concessions will likely result in substantially more pollution. This outcome is due to delayed stricter emissions limits and the retention of an outdated formula for estimating plug-in hybrid emissions.

Delayed emissions limits

The revised regulations allow the average per-mile carbon emissions of light-duty vehicles to be 14% higher between 2027 and 2032 compared to the original proposal. This delay in implementing stricter emissions standards means that higher levels of pollution will persist for several more years than initially anticipated.

Outdated plug-in hybrid formula

The EPA decided to retain a 14-year-old formula for calculating plug-in hybrid emissions until 2031, despite acknowledging that it underestimates real-world pollution. This formula assumes drivers charge their hybrids more frequently and use their combustion engines less than they actually do. Researchers and California regulators estimate that the outdated formula results in emissions estimates that are between 25% to 75% lower than reality.

Incentivising hybrid trucks and SUVs

The lenient treatment of plug-in hybrids could incentivise automakers to produce more of these vehicles, particularly in the truck and SUV segments. Currently, plug-in hybrids account for just 2% of U.S. retail auto sales, while all hybrids make up 11.9%. There are concerns that Detroit automakers, which heavily rely on truck and SUV sales, might introduce plug-in versions of these gas-guzzlers that offer only marginal efficiency improvements.

Automakers’ strategies

Stellantis, which produces Jeep SUVs and Ram pickups, stands to benefit significantly from the hybrid-friendly rules. The company is a leading polluter in the U.S. and the top seller of plug-in hybrids, such as the Jeep Wrangler 4xe. Stellantis argues that its 4xe models provide lower emissions for customers who desire powerful off-road vehicles. The company plans to launch 25 EV models in the U.S. by 2030, including electric versions of the Ram pickup, Jeep Wagoneer, and Dodge Charger.

General Motors (GM) and Ford are also adapting their strategies. GM, which previously avoided hybrids to focus on EVs, now plans to build plug-in hybrids for North America. Ford has seen rising sales of traditional hybrids, including pickups, and sells a plug-in Escape SUV. Both companies expect hybrids to play a more significant role in their future lineups.

Real-world emissions variability

EVs produce zero tailpipe emissions, but the pollution from hybrids varies widely by model. Plug-in hybrids can travel short distances on electric power before switching to gasoline engines. For instance, the Toyota Prius Prime offers 44 miles of electric range and 52 mpg thereafter. In contrast, the Jeep Wrangler 4xe, which is the best-selling plug-in hybrid in the U.S., provides only 21 miles of electric range and 20 mpg thereafter, making it less efficient than its gasoline counterpart.

EPA’s outdated formula

The EPA’s outdated formula gives automakers outsized credit for pollution reductions by assuming drivers charge daily and rarely use gasoline. This assumption does not align with real-world behaviour, where many drivers do not charge their hybrids as frequently. The International Council on Clean Transportation’s senior researcher, Aaron Isenstadt, noted that the real-world use of plug-in hybrids often results in higher emissions than the EPA formula predicts.

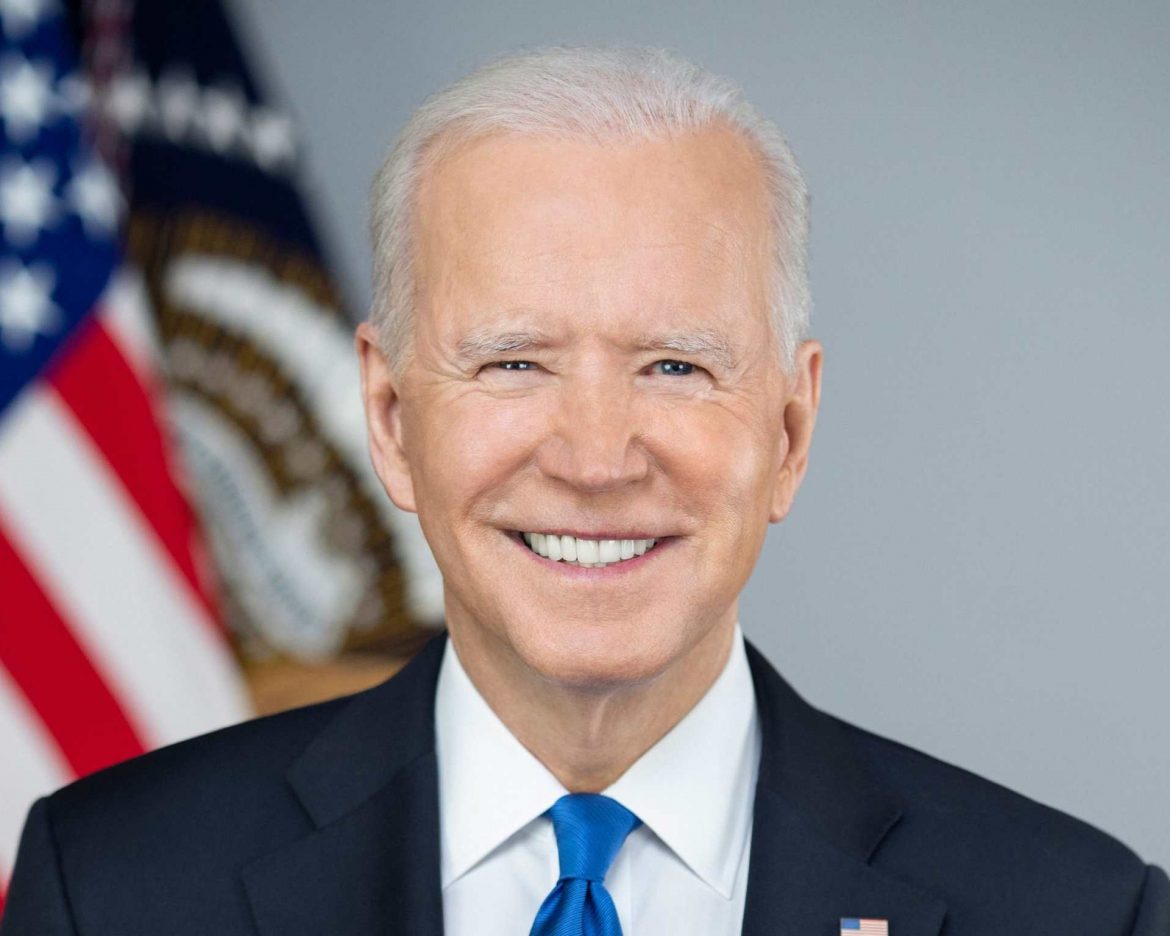

Political considerations

The Biden administration’s adjustment of the emissions rules also reflects political realities. With President Joe Biden seeking re-election and facing pressure from both automakers and political opponents, the administration aimed to balance environmental goals with economic and electoral considerations. The EPA’s original proposal targeted a 67% EV market share by 2032, but the final rules project a range of 35% to 56%, allowing for more flexibility with hybrid engines.

Future of emissions regulations

The EPA’s final rule is expected to achieve 94% of the carbon-emission reductions projected in its original proposal when extended through 2055. However, the effectiveness of these regulations hinges on their longevity and the commitment of future administrations. Historically, automakers have lobbied to delay and weaken strict emissions standards, as seen during the transition from the Obama to the Trump administration.

The Biden administration’s revised auto-emissions regulations represent a compromise between environmental ambitions and industry concerns. While the new rules aim to be achievable and affordable, they may result in higher pollution levels in the short term due to delayed stricter limits and an outdated formula for plug-in hybrids. The impact of these regulations will depend on the auto industry’s response and the political landscape in the coming years. As the market for hybrids and EVs evolves, ongoing scrutiny and potential adjustments to emissions standards will be crucial in driving meaningful progress toward reducing automotive pollution.